In the last couple of months or so, there has been an uptick in posts bashing microservices and confidently stating that all you need is a monolith.

In this post, I will explain why I think microservices have a bad reputation, why monoliths are making a comeback, and what the dangers of monoliths are.

What follows is a bit of a ranty post. If you are looking for rational, technically sound content, consider other posts in this blog and skip this one 🙂

Everybody hates microservices

Except for all the people who have successfully built systems using them for the last 15 years but don’t mind them, focus on the LinkedIn haters who have been posting forever that “all you need is a monolith” and that microservices were wasteful and complex.

These people come in two flavours.

The “I don’t like change” type

Seasoned practitioners decided that microservices weren’t their cup of tea and stuck to their guns. In any other industry, they would face an “adapt or die” challenge and be wiped out of the field. However, Software Engineering has been ballooning for decades; we have absorbed people with all sorts of random backgrounds, and, of course, we haven’t left anyone behind and kept the pseudo-neo-luddites around for good measure.

That said, it is useful to have contrarians around because they serve as a counterbalance to the “happy trigger” techno-optimists who blindly embrace anything new because “new is always better.”

The “Bullshit merchant” type

This is a new phenomenon resulting mostly from the advent of social networks and the rise of personal branding. These guys need to make some kind of noise to be relevant, so why not choose something relatively established and make strident noises about it to capture people’s attention? After all, we live in the attention economy world now.

While the change-resistant folks have a utility as a counterbalance (and, sometimes, early proponents of very serious problems), the bullshit merchants only add noise to the conversation and live to serve their own agenda.

How do you spot them?

- They say things like “I have never seen anything like this in my career”, and they only left university a few years ago.

- They used words like “huge”, “insane”, “incredible”, etc., to describe mundane novelty and/or change.

- They work at consultancy companies (hello, dear McKinsey reader!).

- They have something they want to sell to you, even if you’re not sure what it is (maybe expertise?).

- They post about random events in the world and how they connect to B2C SaaS sales.

Real issues with microservices

Discrediting the people who discredit microservices doesn’t make them the right architectural choice, right? It would also be ridiculous to pretend that microservices are always “the right tool for the job”. There are plenty of cases where you should not use them. Why did it all go wrong?

The unfathomable sizing

Sizing a monolith is easy: you don’t have to. You just dump everything, every line of code, every new feature, there. A whole world of pain is avoided.

SOA architectures predate microservices. Yet, somehow, they managed to avoid the never-ending discussion about sizing. Most likely, because you would have “few enough” services it would be distinctly obvious when it was time to stand a new one up separately. It would be screaming in your face, no choice given.

Microservices, on the other hand, were meant to be “micro”, i.e., small. Otherwise, you would lose their alleged benefits, such as using the appropriate technology stack, offering clear and granular enough boundaries for teams to grow and operate independently, and being able to scale parts of the system separately.

But what was the right size? Nobody knew. One of the OG articles on microservices, Martin Fowler’s blog post, asks the same questions about size without answering them. It’s 10 years old and it is quite telling of what would lay ahead. So many heuristics:

- A two-pizza team should be able to maintain as many microservices as team members.

- Sam Neumman, the father of microservices, proposed its size as something that could be rewritten in two weeks.

- There were various heuristics (which I personally adhere to) based on DDD (Domain-Driven Design) and transactional boundaries to guarantee data consistency and cognitive load balance.

- I once attended a talk where a guy happily claimed to create a new microservice every time he had to implement a new feature at his 2-people startup. God knows what happened to them; surely nothing good.

In other words, nobody knew how to size them. When something is difficult to grasp and doesn’t have clear guidelines, expect the most horrible abuses, followed by undesired side effects and a sudden realization that [insert your technique here] is baaaad.

Getting ready for the improbable success

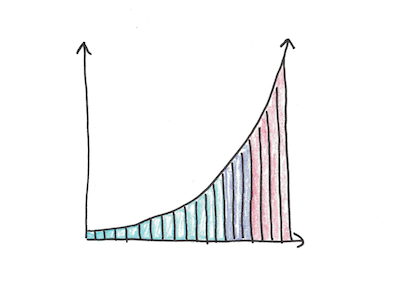

Most startups fail. For those that don’t fail, they don’t achieve planetary scale or experience hockey stick growth.

Microservices were, first and foremost, a tool to scale organisations. They were a sociotechnical architecture pattern that guaranteed that, as companies grew their engineering departments, they would not fall for diminishing returns. Thanks to microservices, people would work and deploy independently in highly cohesive, loosely coupled teams that were aligned to organizational goals. This is what Facebook, Netflix, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, etc., were doing to great success.

Unfortunately, we got the causality arrow wrong. Just like buying a luxurious car doesn’t make you rich, adopting microservices doesn’t make you (or help to be) successful. Successful organisations were forced to adopt microservices (even before they were named) as a consequence of their success (and organisational growth). It was a tax to pay (since microservices, like most things in life, aren’t free lunch) to continue riding the J curve to surreal market valuations.

It follows that adopting microservices as preparation for the inevitable success would be a reverse self-fulfilled prophecy: detrimental to hitting the jackpot.

A long-tail of technologies

While one could implement microservices with the most rudimentary tech stack that already existed in the late 90s and early 2000s, most people ended up dragging a bunch of usual suspects that only increased the suspicion that “microservices were hard” and unnecessarily complex:

- (Docker) containers because you were meant to adopt the right tool for the job, which meant a polyglot stack (Python, Node, Java, Go, etc.)

- An orchestrator to manage those containers, like Kubernetes. This one deserves its own post, as it has come to be seen by many (not me) as a trojan horse planted by Google to slow down the startup ecosystem and maintain technological dominance 🙂

- Polyglot persistence, where NoSQLs like MongoDB would be the key to webscale

- Your favourite cloud provider because managing all those technologies would require an army of DevOps/SysOps, and the cloud provider did all of that for you (for a penny)

- A variety of testing tools to support complex E2E scenarios that didn’t quite exist when you were hitting a single application/service

- Various microservice-related patterns like circuit breakers, sagas, choreography, orchestration, etc.

In other words, we came to associate microservices with many other technologies and tools that were adopted together, even if not always needed, increasing the cognitive overhead for the whole solution.

Why are monoliths back now?

Well, it’s the economy, stupid! Or, more specifically, the end of ZIRP (Zero Interest Rates) and a renewed focus on costs of all kinds.

A part of this is easy to understand: microservices are perceived as expensive, hence why we should ditch them. However, this is the wrong reason to discard microservices. If you believe you need them, the extra cost is significantly smaller than the horrors of not adopting them, slowly grinding your tech department to a hold, incapable of delivering new features or at significantly larger cycles.

What is more interesting is how the end of ZIRP will affect organisations’ bottom line. For years, “growth” was the only metric: more customers and more market share. There was a drive to grow organisations, offer more products and continue in this virtuous cycle until some kind of exit; revenue and profit were an afterthought, something that would materialise eventually. If it worked for Google or Amazon, why wouldn’t work for me? This added a lot of pressure for tech departments to scale: hire more engineers, onboard them as fast as possible, and continue launching.

The part is over, though.

VCs and other liquidity providers want to see results in the short term instead of some fantastic future growth that never materialises into ROI. They want more revenue and more profit for the same (or less) investment. That means “doing more with less” (as every CEO puts it) or, in other words, forgetting about hiring/growing and doubling the workload on your existing staff. If you don’t like it, go join the long queue of engineers who have been laid off from busted startups and “more nimble, prepared for future growth” FAANG companies.

In this context, you probably need microservices less often than before. If you don’t have to solve an organisational scalability problem and nothing suggests you are gonna be one of the unicorns that experience tremendous demand growth, why would you jump on that wagon?

You probably started with a single service anyway. Stick to it for as long as it makes sense and ignore the labels.

Is that it? No more microservices?

Are we gonna worship monoliths now like we once (mostly) worshipped microservices?

I truly hope not. I was part of the industry before microservices were given a name. I have seen some absolutely horrendous codebases that could only be deployed every 3+ months because they were too big and too bloated to do any more often. I have also been involved in a few “microservices migrations” where the company would try to transition away from the monolith(s); spoiler alert, it was NOT pretty, and it was NOT successful. If people advocating blindly monoliths over microservices think that is progress, they don’t know what they are talking about.

Maybe what they call “monolith” is your ever-slightly enlarged, quite-young-startup microservice. Comparing that to a microservice would be like comparing your dog to a T-Rex

If they had truly experienced monoliths (the Airbus 380 type ones), they would not be happily advocating them. For all the “distributed monolith” systems out there, we have 10x more monoliths that have taken / will take years to migrate to appropriate architectural approaches because the hardest problem is always the data (and yes, it is also for microservices, as Christian Posta called out 5 years ago).

My recommendation is to ask lots of questions to the business/product department, dig as deep as possible into future growth plans (particularly head counts) and draft an architectural roadmap that accounts for that. If your whole engineering department is a single team of colocated developers, don’t even think about microservices.

If your company is planning to open multiple offices and hire developers across the globe in separate time zones, you need to start considering patterns that enable people to work as asynchronously as independently as possible. Can you do that with a monolith? Sure. Is it easier to do than adopting microservices? Unlikely.

There is a time and place for microservices, just as there is for monoliths. Anyone pretending otherwise is not to be trusted.

One thought on “You probably don’t know monoliths”