We discussed naming conventions for Kafka topics and Kafka Producers/Consumers in the previous two posts. This time, we are focusing on Kafka Connect and the connectors running on it.

We will not discuss naming conventions related to Kafka Connect clusters (e.g., config/storage/offset topic names,

group.id, etc.) They are normally managed by SysAdmin/DevOps teams and these posts are zooming in developer-related naming conventions.

Kafka Connect in a few words

What is Kafka Connect?

Kafka Connect is a tool for streaming data between Apache Kafka and external systems, such as databases, cloud services, or file systems. It simplifies data integration by providing a scalable and fault-tolerant framework for connecting Kafka with other data sources and sinks, without the need to write custom code.

In other words, Kafka doesn’t exist in a vacuum; there are different “non-Kafka” systems that it needs to interact with, i.e., consume from and produce to. Kafka Connect simplifies this task massively by offering “connector plugins” that will translate between:

- Protocols: SFTP->Kafka, Kafka->SFTP, Kafka->HTTP, Salesforce API->Kafka, etc.

- Formats: CSV->Avro, Avro->JSON, Avro->Parquet, etc.

Theoretically, Kafka Connect can also translate between schemas (i.e., data mapping) via Single Message Transformations. However, I advise against using them except for the most trivial transformations.

Kafka Connect defines two types of connectors:

- Source connectors consume data from non-Kafka systems (e.g., databases via CDC, file systems, other message brokers) and produce it for Kafka topics. These connectors are “Kafka producers” with a client connection to the source data system.

- Sink connectors consume data from Kafka topics and produce it to non-Kafka systems (e.g., databases, file systems, APIs). Internally, they work as “Kafka Consumers” with a client connection to the destination system.

Naming Conventions

Now that we have a basic understanding of Kafka Connect let’s examine the most relevant settings that require precise, meaningful naming conventions.

connector.name

This is obviously the “number one” setting to define. A few things to consider:

- It has to be globally unique within the Connect cluster. In other words, no connector in the cluster can share the same name.

- It is part of the path to access information about the connector config and/or status via the Connect REST API (unless you use the

expandoption and get them all at once). - For Sink connectors, it serves as the default underlying consumer group (plus a

connect-prefix). In other words, if your connector is calledmy-connector, the underlying consumer group will be calledconnect-my-connectorby default.

With that in mind, the proposed naming convention is as follows:

[environment].[domain].[subdomain(s)].[connector name]-[connector version]

| Component | Description |

environment | (Logical) environment that the connector is part of. For more details, see https://javierholguera.com/2024/08/20/naming-kafka-objects-i-topics/#environment |

domain.subdomain(s) | Leveraging DDD to organise your system “logically” based on business/domain components. Break down into a domain and subdomains as explained in https://javierholguera.com/2024/08/20/naming-kafka-objects-i-topics/#domain-subdomain-s |

connector-name | A descriptive name for what the connector is meant to do. |

connector-version | As the connector evolves, we might need to run side-by-side versions of it or reset the connector completely giving it a new version. Format: vXY (e.g., ‘v01’, ‘v14’). This field is not mandatory; you can skip it if this is the first deployment. |

Do we really need [environment]?

This is a legit question. We said that the connector name must be (globally) unique in a given Kafka Connect cluster where it is deployed. A Kafka Connect cluster can only be deployed against a single Kafka cluster. Therefore, it can only sit in a single (physical) environment. If that is the case, isn’t the “environment” implicit?

Not necessarily:

- Your Kafka cluster might be serving multiple logical environments (DEV1, DEV2, etc.). As a result, a single Kafka Connect cluster might be sitting across multiple logical environments even if it belongs to a single physical environment. In this deployment topology, you might have the same connector in multiple logical environments, which would require the

[environment]component to disambiguate and guarantee uniqueness. - Alternatively, you might deploy multiple Kafka Connect clusters serving single logical environments against a single (physical) Kafka cluster. You might be tempted to think in this scenario

[environment] is not needed since the connector name will be unique within its cluster. However, “behind the scenes”, sink connectors create a Kafka Consumer whose name matches the connector name (plus aconnect-prefix). Therefore, if multiple Connect clusters with the same connector name create the same Kafka Consumer consumer group, all sort of “issues” will arise (in practice, they end up either forming a big consumer group targeting the topics across all logical environments in that physical Kafka cluster).

In summary, if you don’t use any concept of “logical environment(s)” and can guarantee that a given connector will be globally unique in the Kafka cluster, you don’t need the [environment] component.

consumer.override.group.id

Starting with 2.3.0, client configuration overrides can be configured individually per connector by using the prefixes producer.override. and consumer.override. for Kafka sources or Kafka sinks respectively. These overrides are included with the rest of the connector’s configuration properties.

Generally, I don’t recommend playing with consumer.override.group.id. Instead, it is better to give an appropriate name to your connector (via connector.name), as per the previous section.

However, there might be scenarios where you can’t or don’t want to change your connector.name yet you still need to alter your default sink connector’s consumer group. Some examples:

- You have already deployed your connectors without

[environment]in yourconnector.name(or other components) and now you want to retrofit them into your consumer group. - You have strict consumer group or

connector.namenaming conventions that aren’t compatible with each other. - You want to “rewind” your consumer group but, for whatever reason, don’t want to change the

connector.name.

In terms of a naming convention, I would recommend the simplest option possible:

[environment or any-other-component].[connector.name]

In other words, I believe your consumer group name should track as closely as possible your connector.name to avoid misunderstandings.

consumer/producer.override.client.id

client.id was discussed in a previous post about Producer’s client.id and Consumer’s client.id.

As discussed in that post, it is responsible for a few things:

- Shows up in logs to make it easier to correlate them with specific producer/consumer instances in an application with many of them (like a Kafka Streams app or a Kafka Connect cluster).

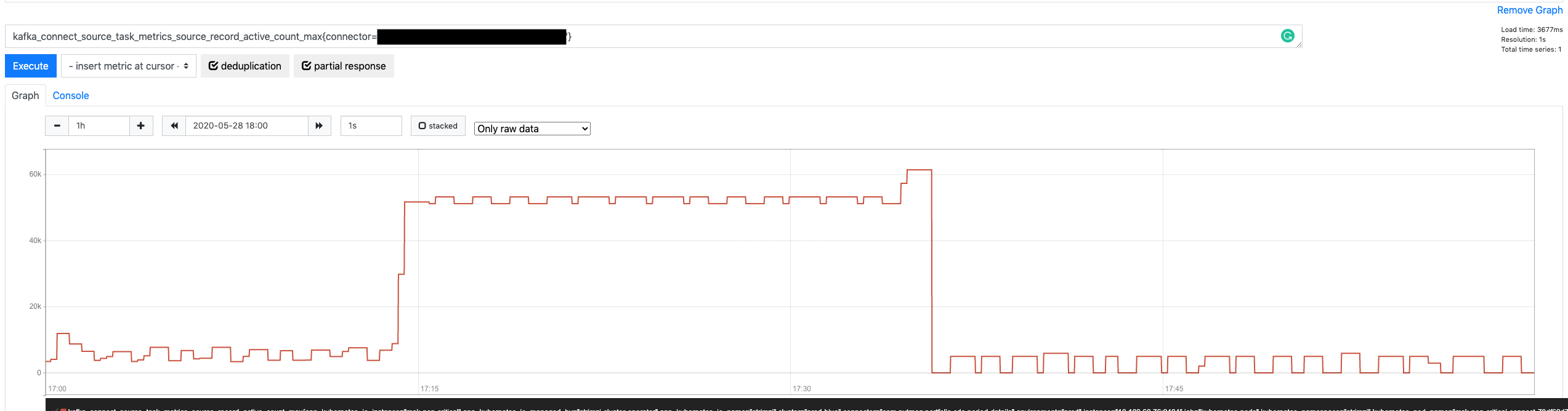

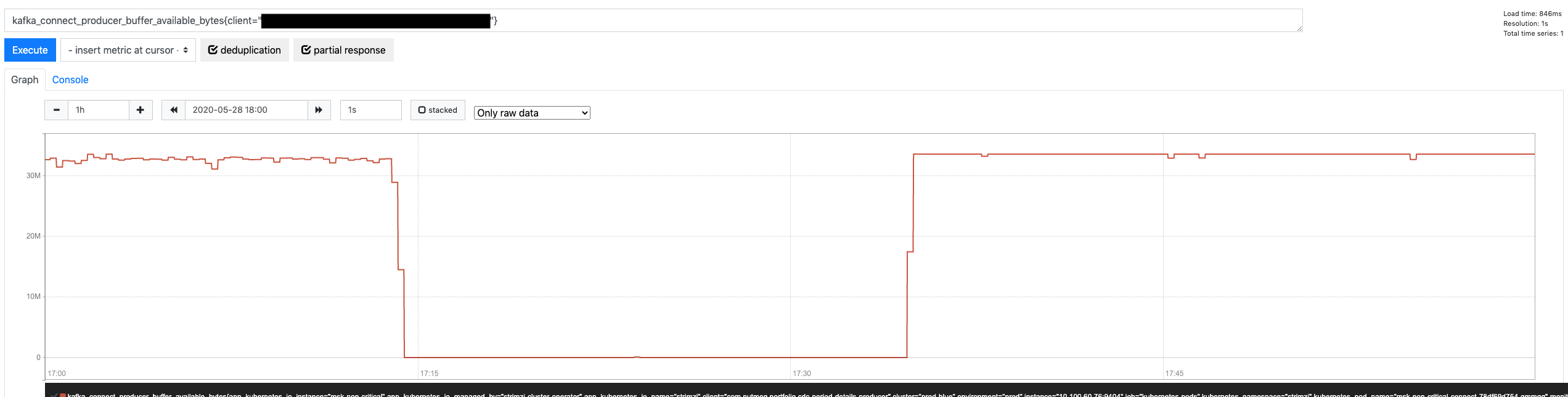

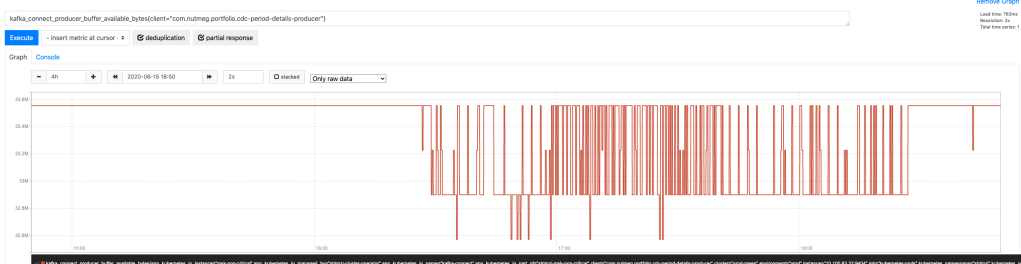

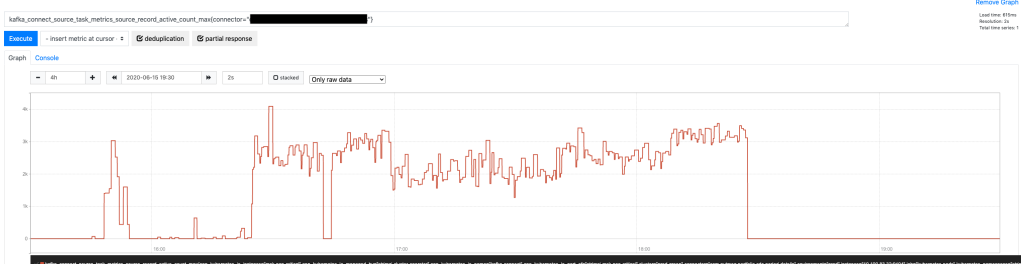

- It shows up in the namespace/path for JMX metrics coming from producers and consumers.

With that in mind, knowing that we already have a pretty solid, meaningful and (globally) unique connector.name convention, this is how we can name our producer/consumer client.id values.

| Connector Type | Property Override | Value |

| Source connector | producer.override.client.id | {connector.name}-producer |

| Sink connector | consumer.override.client.id | {connector.name}-consumer |

Conclusion

We have discussed most relevant properties that require naming conventions in Kafka Connect connectors. As usual, we aim to have semantically meaningful values that we can use to “reconcile” what’s running in our systems and what every team (and developer) owns and maintains.

By now, we can see emerging a consistent naming approach rooted around environments, DDD naming conventions and some level of versioning (when required).