Many developers believe that events inherently offer advantages over other message types, such as commands, making them “better” by default. In other words, they think that messaging between services should heavily rely on events while minimising the use of commands.

In this article, I aim to dispel that myth. As is often the case, the correct answer is: “It depends.” Neither events nor commands are inherently superior; each is best suited to specific scenarios.

- Commands are from Mars, Events are from Venus

- Coming from the left or the right side

- How does a “good” event look?

- What is the “passive-aggressive” event?

- Events enable decoupling, commands don’t?

Commands are from Mars, Events are from Venus

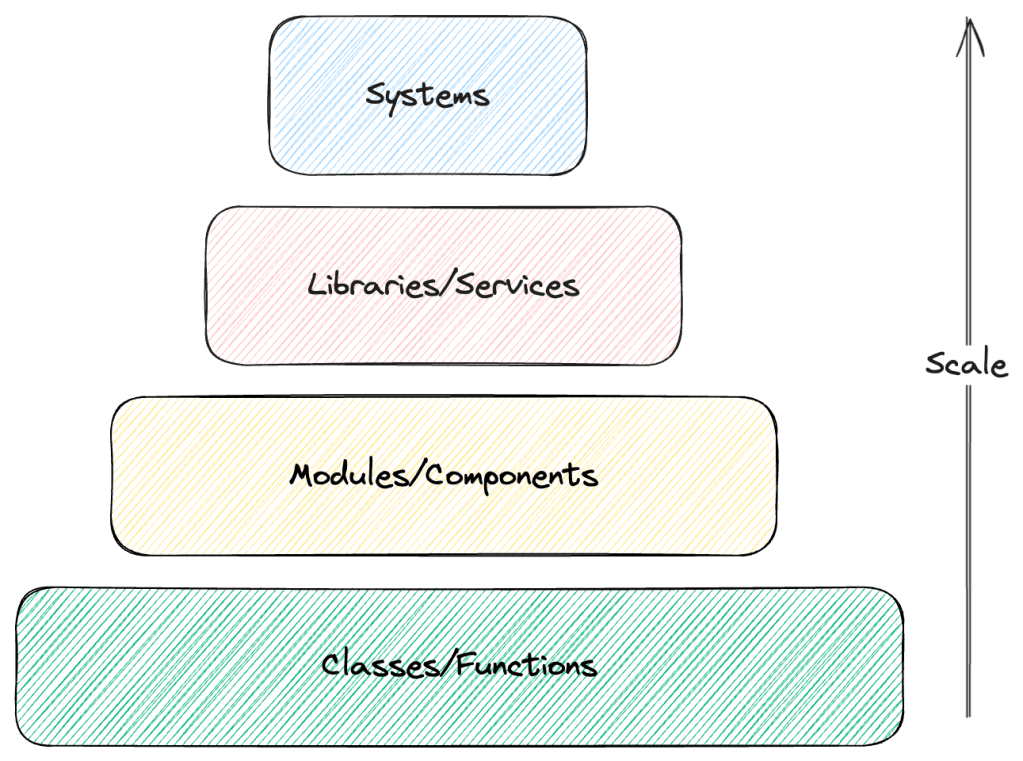

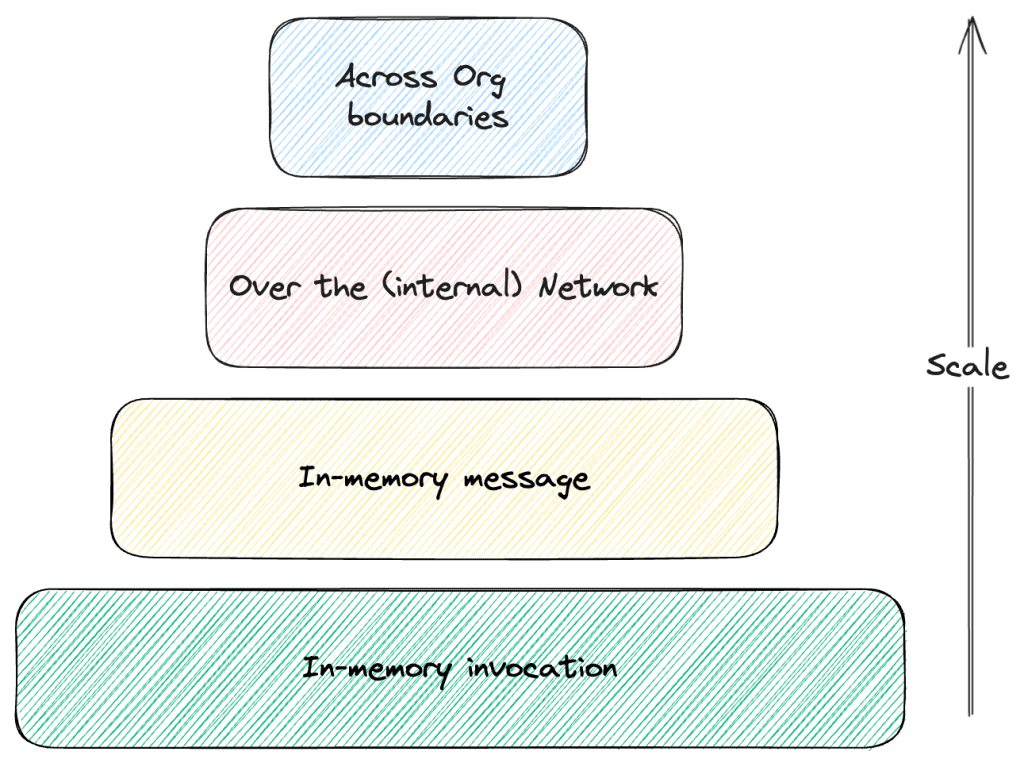

Clemens Vasters, Principal Architect of Azure Messaging Systems (Azure Service Bus, Azure Event Hubs, etc.), proposed a classification of distributed messaging types that I find particularly insightful. He divides them into two categories:

- Intents (left column): Reflect a transfer of control from one service to another, such as commands and queries.

- Facts (right column): Represent something that has happened in the past and, as such, cannot be retracted. Domain events (such as in Event Sourcing) fall into this category.

Coming from the left or the right side

Most developers start their distributed messaging journey, favouring one side over the other: either systems dominated by “intents” (especially commands) or fundamentally “event-driven” choreographies and orchestrations.

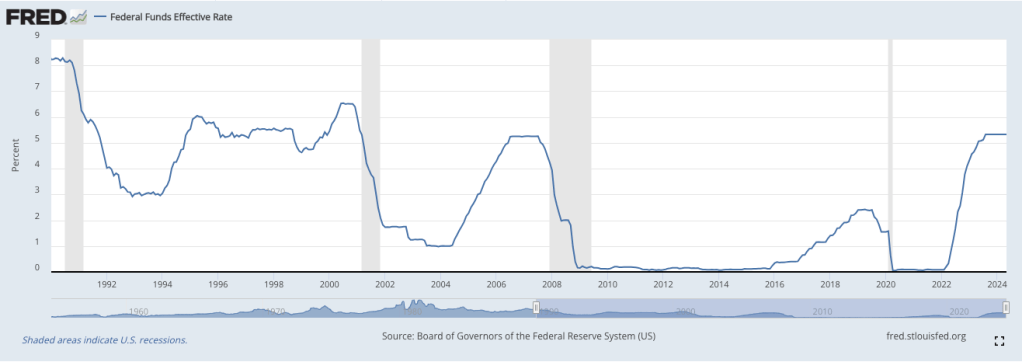

Until about five years ago, your first experience with distributed messaging was likely using brokers like SQS or RabbitMQ to queue commands and load-balance work across worker pools. Applications at the time were less data-intensive and more focused on behaviour and interaction.

Then came the Big Data movement, “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” (DDIA), and Kafka. Suddenly, we modelled systems as data flows represented by events. Data was king, and systems became a series of computations built on top of data movements.

Regardless of how your journey began, it likely left you with a “blind spot” toward the other side. If you started with events, everything looked like an event. If you started with commands, everything looked like a command.

I know this firsthand; I spent ten years primarily building event-driven systems, where events were foundational and Kafka was the default transport layer. Over time, I noticed the emergence of a problematic pattern I call the “passive-aggressive” event.

How does a “good” event look?

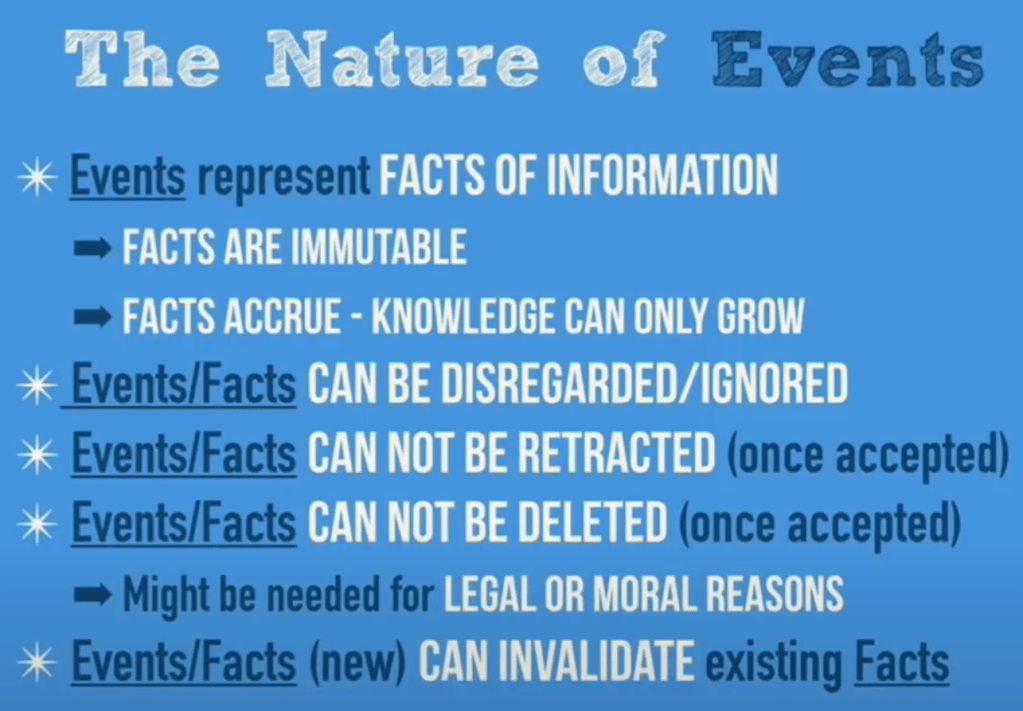

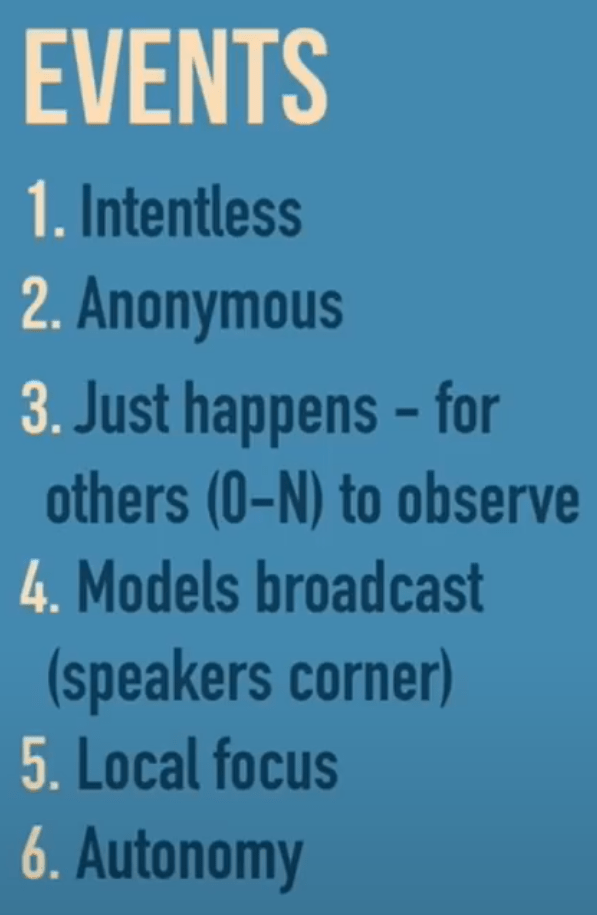

Before we understand the “passive-aggressive” event anti-pattern, we need to define what a good event is. Jonas Bonér offers a helpful perspective in his legendary Voxxed Days talk on how events are reshaping modern systems.

In short:

- Events represent facts from the past and, therefore, cannot be changed. However, they can be corrected and accumulated.

- Events are broadcast without any expectations from the producer about what consumers will do. In fact, the producer neither knows nor cares who the consumers are (Bonér describes this as “anonymous”).

This model supports greater system autonomy and decoupling. However, “can” is the operative word—abusing events can lead to an “insidious” form of coupling.

What is the “passive-aggressive” event?

In simple terms, a “passive-aggressive” event is a command improperly modelled as an event. The giveaway is when the producer cares about the consumer’s reaction or expects feedback.

In proper event modelling, the producer should have zero expectations about how or whether the event is handled. In a passive-aggressive event, a hidden “backchannel” exists where the producer expects actions or responses from the consumer.

Let’s explore this with an example.

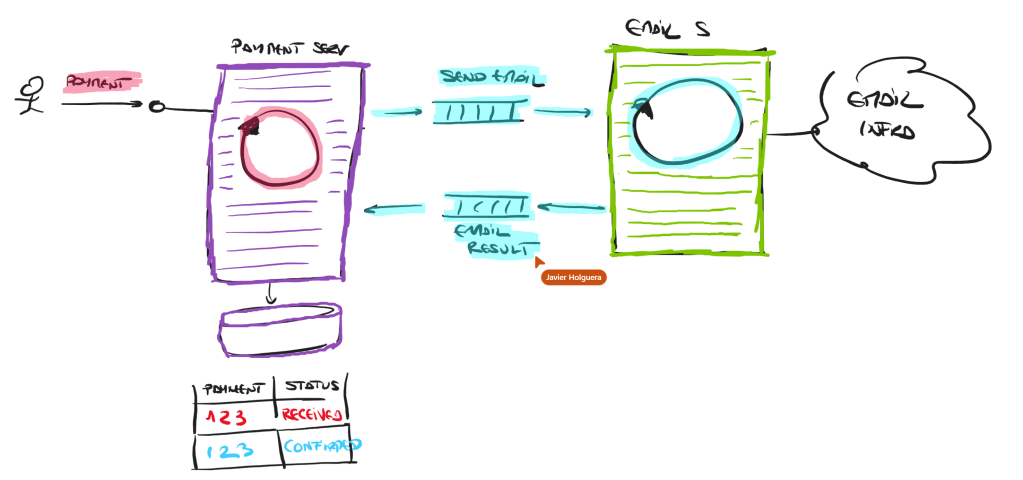

Imagine an application that manages payments. When money is received, it is flagged as “Received.” Upon reception, we want to notify the sender by email. Once the email is sent, the payment is moved to “Confirmed.”

There are two services:

- A Payment Service that manages the payment lifecycle.

- An Email Service responsible solely for sending emails.

Modelling with an event

Let’s model this interaction with an event first.

Flow:

- A user sends a payment.

- The Payment Service receives and stores it as “Received.”

- It broadcasts an event: “PaymentReceived.”

- The Email Service consumes the event, sends an email, and then emits a “PaymentConfirmed” event or calls the Payment Service directly to update the payment state.

Using a command instead

Let’s model it with a command now.

Flow:

- A user sends a payment.

- The Payment Service receives and stores it as “Received.”

- The Payment Service sends a command to the Email Service: “SendConfirmationEmail.”

- The Email Service processes the request and responds with a success or failure message.

- The Payment Service updates the payment state to “Confirmed” based on the response.

Why does it matter?

The second model maintains better encapsulation (a principle emphasised by David Parnas since the 1970s). In the event model, business logic leaks into the Email Service, breaking the Payment Service’s encapsulation and increasing the cost of change.

Furthermore, the Email Service becomes less reusable because it must understand business logic unrelated to email delivery.

If this approach is repeated across integrations—e.g., linking Email Service with User Account Service, Bank Account Service, and so on—it becomes unsustainable, leading to a “Distributed Monolith”: the worst aspects of monoliths and microservices combined.

Clear boundaries and separation of concerns (echoing SOLID’s Single Responsibility Principle and DDD’s Bounded Contexts) improve organisational flow and reduce cognitive load. Clean, explicit contracts facilitate easier understanding and modification.

Events enable decoupling, commands don’t?

Many like to repeat this mantra, but it is misleading.

Encapsulation is what enables decoupling. Encapsulation allows systems to integrate via low-touch interfaces, exposing only what is necessary.

In our example, using a command allows the Payment Service to know only the minimal information needed to send an email. The Email Service is concerned solely with sending emails, not with the reason behind the email being sent.

Does this mean we should always prefer commands to events? Absolutely not. When it’s safe to simply publish an event and let downstream consumers react (or not), events are preferable. However, we must be cautious not to inadvertently increase coupling through hidden dependencies and back channels.