If you’ve ever worked on a data integration project and felt overwhelmed by all the moving parts, you’re not alone. It’s easy to get lost in the details or to over-engineer parts that don’t really need it.

This post introduces a simple model that can help you make sense of it all. By breaking data integrations into three clear levels (protocol, format, and schema), you’ll be better equipped to focus your energy where it matters and rely on proven tools where it doesn’t.

What is a “Data Integration”?

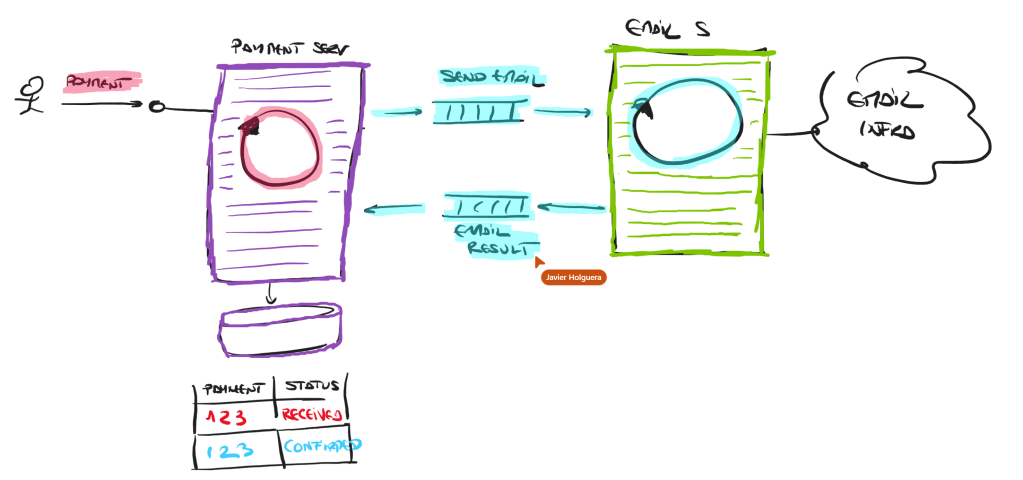

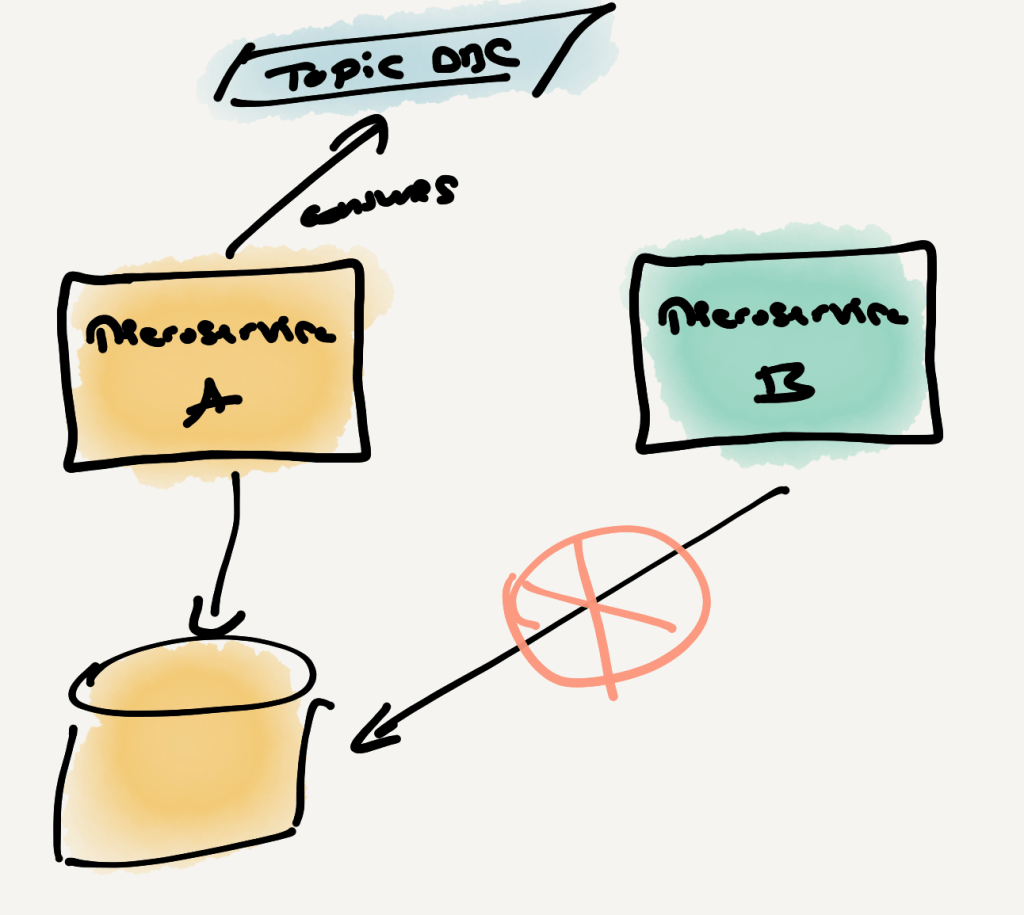

Whenever two systems connect or integrate, they inevitably share some form of information. For example, if System A requests System B to process a payment, System A must provide certain data for the payment to proceed.

However, this kind of functional exchange is not what I define as a “Data Integration.” Instead, a Data Integration occurs when the primary goal is to share data itself, rather than invoking another system’s functionality. In other words, Data Integration refers specifically to integrations where one system consumes data provided by another, rather than utilizing that system’s behavioral capabilities.

We now live in a world dominated by data-intensive applications, making Data Integrations the most critical form of system integration. These integrations have displaced traditional functional integrations, which used to prevail when data was less ubiquitous and valuable.

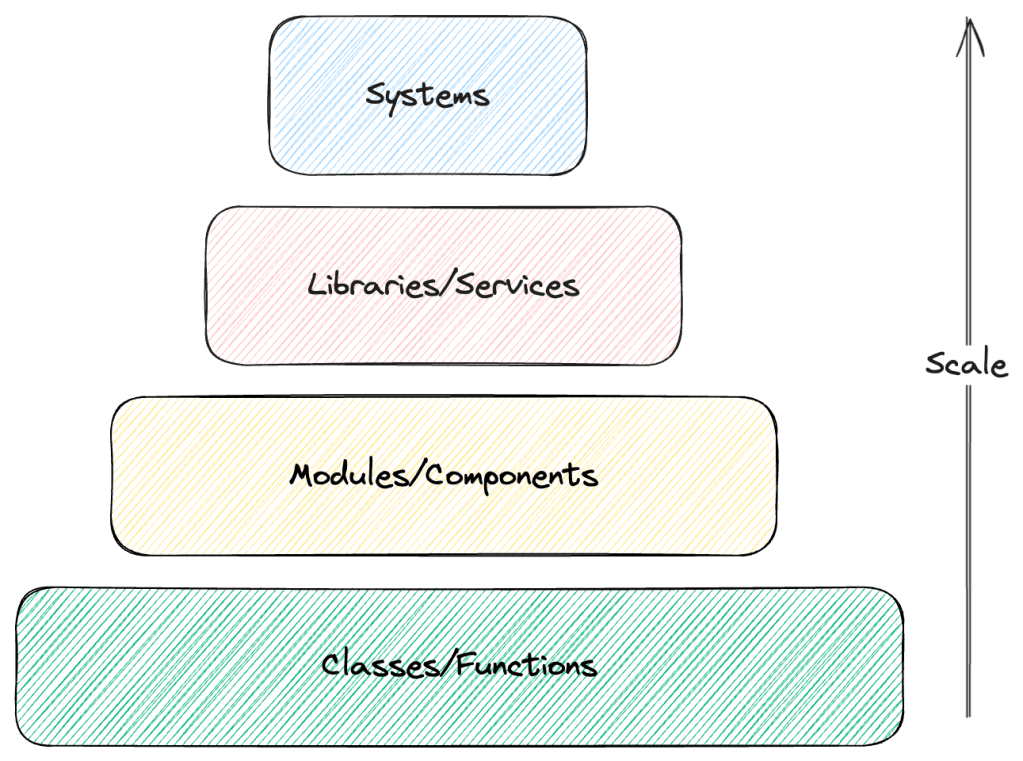

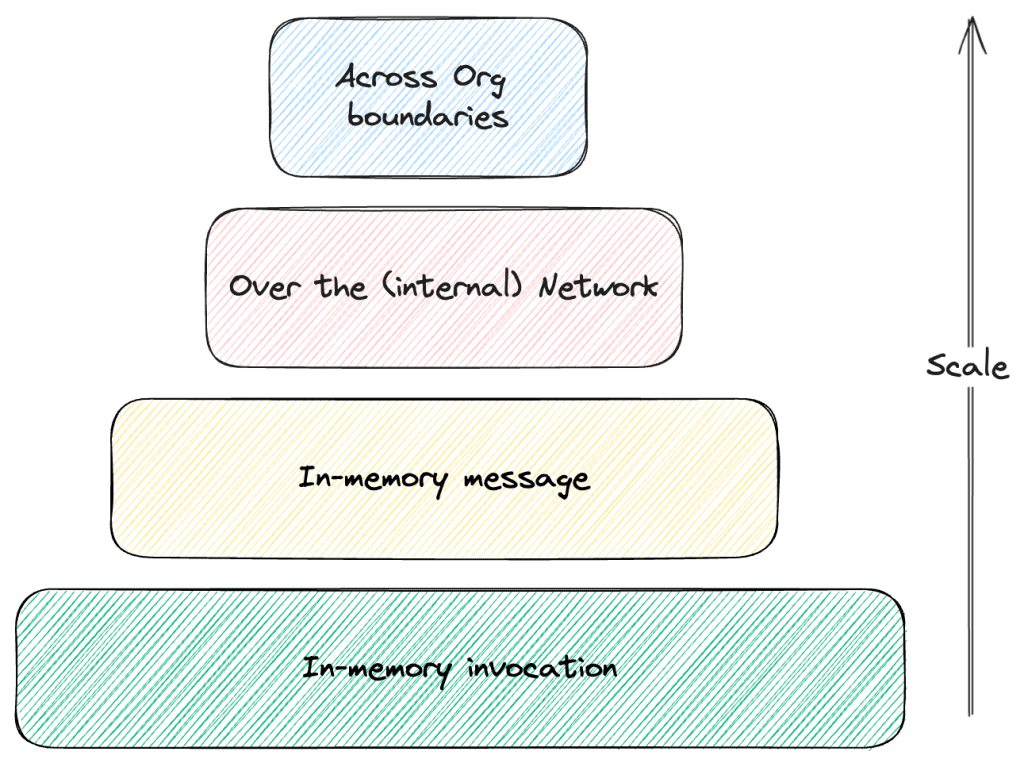

A 3-level model for data integrations

Every data integration can be broken down into three levels or layers, each with distinct responsibilities (and constraints). The beauty of it is that they are (almost) completely independent of each other and exchangeable.

Protocol Level

This is the foundational level and it is all about “exchanging bytes” between systems, without concern for anything else.

This layer is typically hidden behind higher-level abstractions and, while all abstractions leak, you can be generally confident that you won’t need to look under the hood to check out what is happening here and how it works. Things just work.

Examples of protocols:

- HTTP(s), which powers all REST-based APIs.

- SMTP to exchange emails.

- (s)FTP to exchange files.

- Proprietary protocols, like those powering technologies like SQL Server, PostgreSQL, Apache Kafka, Google’s gRPC, etc. They tend to be built on top of TCP.

As with all technologies, the more established a protocol is, the stronger and more reliable its abstractions become, requiring you to know less about underlying details.

However, technology is subject to The Lindy Effect (the idea that longevity indicates future durability); therefore, investing time learning these protocols will result in the highest ROI for your professional career.

Format Level

The next level is all about giving shape to those bytes. In other words, if we were to make an analogy with human communication, protocols are about deciding whether to talk by phone or to exchange letters, while formats are about choosing the language used (e.g., English, Spanish).

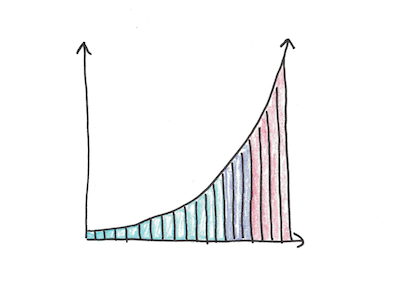

There is a long tail of formats, some more established, some more recent (and immature). There is also a surprising amount of “variability” in some well established formats when it comes to what is (generally) considered acceptable (for example, JSON’s loose specification has introduced significant variability).

Examples of formats:

- Good old text in UTF-8 or any of its derivates (e.g., UTF-16, UTF-32).

- Internet/Web formats like JSON or XML.

- File exchange formats like CSV.

- Modern formats for Big Data (Avro, Parquet), RPC (Protocol Buffers, Thrift, MessagePack), etc.

- Proprietary formats, like what technologies like SQL Server or PostgreSQL use to send information back and forth between client and server.

While some of these formats will get regularly paired with certain protocols (for example, HTTP/JSON, CSV/SFTP, Kafka/Avro, gRPC/Proto), in many cases they are completely decoupled and can be swapped. For example, it’s entirely possible to use XML with HTTP, upload Avro files to an SFTP server or write a CSV as a UTF-8 message to Kafka (if you are crazy enough to consider it).

Schema Level

The final level, where application-specific logic and business requirements become concrete. In other words, this is the level where your specific use case, business scenario, API specification, etc. becomes reality. No abstraction, no commoditization, you are doing all the work here.

In this level you need to do things like:

- Data modelling to create schemas and data structures representing your business entities and relationships.

- Data transformations to convert input schemas map to output schemas, including rules for data enrichment, filtering, aggregation, or reformatting.

- Implement non-functional requirements like:

- Identify sensitive and non-sensitive data, ensuring compliance with security standards.

- Clarify how frequently data is refreshed (e.g., daily, hourly, near-real time).

- Track where data originated and how it has been transformed or moved.

How is this model useful?

There are several reasons why this three-level model is particularly useful for Data Integrations:

Clear separation of concerns

Each level has distinct responsibilities, making complex integrations easier to understand and manage. Engineers can tackle each level independently, enabling parallel work. Different engineers can focus simultaneously on different levels without conflicts.

Improved reusability

Since each level is independent and components at any level can easily be swapped, it becomes simpler to reuse existing code, expertise, and infrastructure.

For example, if an existing integration uses HTTP with JSON, it requires minimal effort to replace the JSON serializer with an XML serializer, while continuing to leverage the existing protocol-level (HTTP) and schema-level implementations.

Targeted commoditization

The Protocol level, as defined, is the most mature and heavily abstracted. Similarly, the Format level is also mature in most scenarios. This maturity drives commoditization, enabling the use of standard, off-the-shelf technologies to handle conversions between protocols and formats with minimal custom code.

For instance, technologies like Azure Data Factory or Apache Airflow can convert seamlessly between SMTP and HTTP, or between XML and JSON, using no-code or low-code interfaces, provided schema-level details remain the same.

This commoditization accelerates Data Integration development and allows engineers to concentrate on schema-level transformations, where the real business logic resides.

Summary

In this post, I shared a model for thinking about Data Integrations that has served me well over the years. It may not be the most sophisticated, but its simplicity makes it practical: it helps you distinguish the parts that truly require your attention (like the schema level) from those you can reliably delegate to off-the-shelf technology (such as the protocol and format levels).