I know, we don’t like microservices anymore, and they are out of fashion. However, I still think about how I was trying to build them until the sudden change in industry fashion convinced me that building modular monoliths was entirely different from how monoliths were meant to be built in the past.

In this post, I want to reflect on a few broad roles I follow(ed) when building microservices. I believe broad rules and flexible heuristics are appropriate when making architectural decisions because context (e.g., business, technical, human) is more critical than (blindly) following rules.

- What is a microservice?

- Rule 1 – Teams don’t share microservices

- Rule 2 – Microservices don’t share (private) data storage

- Rule 3 – Avoid distributing transactions through the network

- Rule 4 – Network latency adds up

- Rule 5 – No Service to Service calls between services

- Conclusions

What is a microservice?

We should first qualify what a microservice represents.

Most people equate a microservice with a single service deployable. For example, my microservice is a REST API web server receiving traffic on port 8080. This is not the right way of thinking about microservices because microservices weren’t invented as a technical concept but as a sociotechnical one, a solution to the organisational scalability problem (in a technical context, nonetheless).

The rules that define microservice boundaries cannot be purely technical (albeit this is a crucial factor); they also need to incorporate aspects like team structure, cognitive load, product boundaries, geographical boundaries, etc.

Therefore, it becomes easier to define what a microservice is not:

- A microservice is not a single process (e.g., a single JVM running in a container).

- A microservice is not a single deployable (e.g., a single Docker image).

- A microservice is not defined in a single repository (e.g., Github).

On the contrary, the following things are perfectly possible:

- One microservice runs as multiple processes because, in its Kubernetes pod, we also have sidecar containers performing roles like Service Mesh, Ambassador, etc.

- Multiple deployables working in coordination define one microservice. For example, in a CQRS or Event Sourcing architecture, you might separate your command handler and/or writer model producer from your query handler and/or event consumer.

- If we choose to use a company-wide mono repo or product mono repos (all parts of a given product), one repository contains multiple microservices.

To summarise these rules, we can say:

A Microservice is an application (i.e., a logical boundary for behavior represented by code and state resources) that is developed, deployed and maintain together.

Rule 1 – Teams don’t share microservices

In other words, every microservice has only one team that owns it.

This principle doesn’t rule out any of the following:

- Multiple teams (and their products) depending on a given microservice. This is fine because it doesn’t change the fact that only one team owns the microservice.

- Multiple teams contribute to the microservice code. This, too, is okay, provided the team that owns the microservice is happy to support some kind of coordinated contribution process (like the Inner Source model).

For reasons of accountability, only one team must own a service. We trust teams to build services and run them in production; in exchange, we must empower them to make the right decisions (within whatever architectural framework the company has adopted).

This empowerment is voided if it doesn’t come with the necessary accountability for the consequences of those decisions. “Sharing” ownership, at a minimum, deludes accountability; at worst, it completely prevents it.

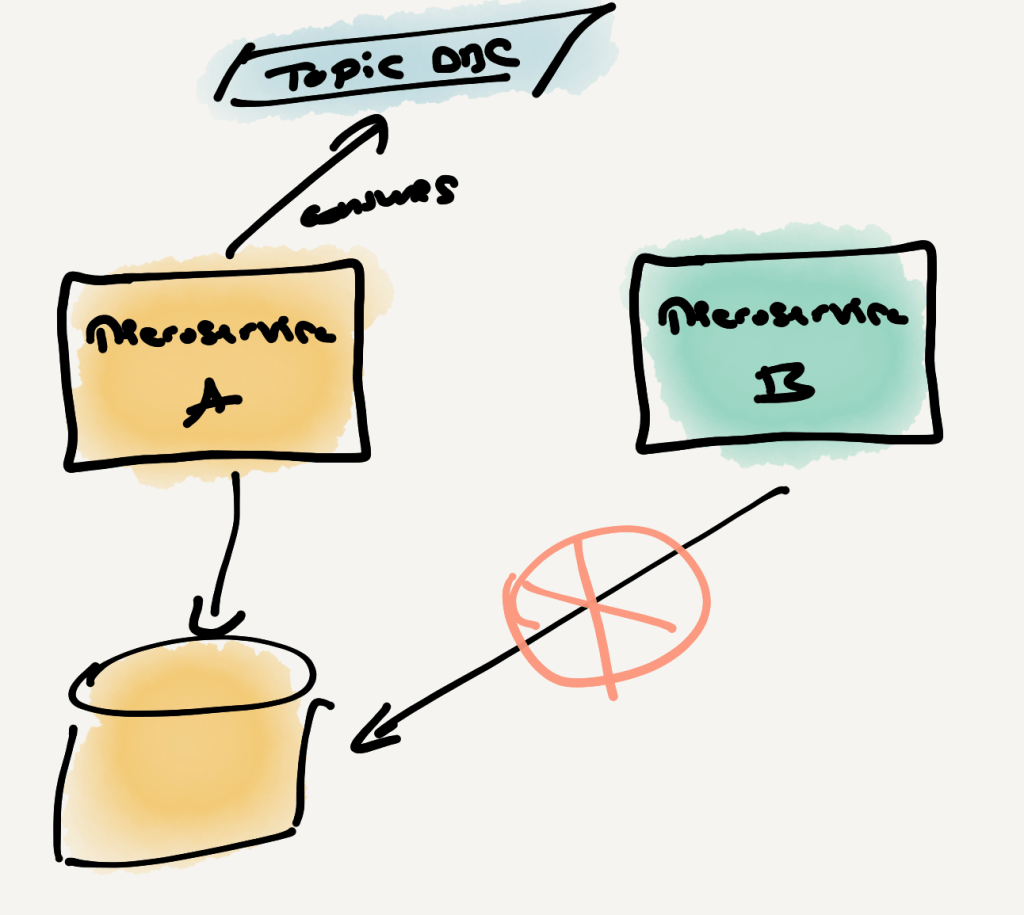

Rule 2 – Microservices don’t share (private) data storage

Private data storage is where a single microservice stores information for execution. This can be master data for lookups, historical payments data for de-duplication and/or state validation, etc.

Microservices must be able to change the schema of their data storage freely; after all, it is their private concern.

We achieve this by ensuring that two microservices never share the same private data storage.

Public vs private data storage

It is important to differentiate what private data storage is and when we see it as public.

Private data storage is created to support the functionality of a microservice; when the microservice logic changes, the storage (might) also change. Private data storages contain private data designed to be consumed by the microservice but not shared or available to other microservices. Private data storages don’t make any promises regarding schema changes (e.g., backward compatibility, forward compatibility) beyond what the single microservice requires. To sum up, private data is an implementation concern.

Public data storage is the opposite of what is described above: it is designed for sharing, uses schemas with compatibility guarantees, and is easy to consume. In other words, public data is an API.

The following table contains some examples of public and private data storage:

| Storage | Type | Description |

| Private Kafka Topics | Private | Akin to tables in a private database. For an explanation of what a “private topic” means, see: https://javierholguera.com/2024/08/20/naming-kafka-objects-i-topics/#visibility |

| Shared/External Kafka Topics | Public | Akin to REST API endpoints. For an explanation of what a “shared/external topic” means, see: https://javierholguera.com/2024/08/20/naming-kafka-objects-i-topics/#visibility |

| Private Blob Storage (S3/Azure Blob Storage) folders | Private | Only used by a single microservice and/or application |

| Public Blob Storage (S3/Azure Blob Storage) folders | Public | Produced by one microservice, available for others to read. |

| Relational databases | Private | Only used by a single microservice and/or application. |

| NoSQL databases | Private | Only used by a single microservice and/or application. |

| Like-for-Like shared/external Kafka topics sunk into databases | Public | This is a particular case of the above. If a topic producer decides to offer a “queryable” version of the same data as a (SQL/NoSQL) database and it is captured as a like-for-like sink of a shared/external topic, it is public because: – Its schema will follow the same compatibility rules as the Kafka topic(s). – Its database (and tables/containers) are provisioned exclusively for sharing purposes, not as a private concern of any specific microservice. |

Avoiding resource contention

Another reason for separating microservices databases is to avoid resource contention.

In a scenario where two microservices share the same database (or other infrastructure resources), it can run into Noisy Neighbour antipattern problems:

- Application A receives a spike of traffic/load and starts accessing the shared resources more intensely.

- Application B starts randomly failing when it cannot access the shared resources (or it takes longer than it can tolerate, leading to timeouts).

Ensuring every microservice accesses independent resources guarantees we don’t suffer these problems.

This principle can lead to increased infrastructure costs. For that reason, it is perfectly reasonable to consider the following exceptions:

- Reuse underlying infrastructure in environments before the production environment, where the consequences of occasional resource contention are not particularly worrying.

- Reuse underlying infrastructure between services whose volume is expected to be low. As long as the microservices aren’t coupled at the logical level (i.e., the data itself, not the storage infrastructure), it is relatively easy to “separate” their infrastructure in the future if required (compared to separating them if coupled at the logical schema level).

For the last point, I would advise against doing this with microservices shared by somewhat distant “organizationally” teams (e.g., crossing departments or division boundaries, minimum timezone overlap, or any other barrier that prevents fluid communication).

Rule 3 – Avoid distributing transactions through the network

I always recommend considering DDD heuristics to drive your microservice design. I use the DDD “Aggregate Root” concept to help me model microservices and their responsibilities. DDD defines “Aggregate Root” as follows:

An Aggregate Root in Domain Driven Design (DDD) is a design concept where an entity or object serves as an entry point to a collection of related objects, or aggregates. The aggregate root guarantees the consistency of changes being made within the aggregate by forbidding external objects from holding references to its members. This means all modifications within the aggregate are controlled and coordinated by the aggregate root, ensuring the aggregate as a whole remains in a consistent state. This concept helps enforce business rules and simplifies the model by limiting relationships between objects.

An aggregate root should always have one single “source of truth”, i.e., one microservice that manages its state (and modifications). We want this because it means we avoid (as much as possible) distributing transactions over multiple services (through the network).

The alternative (i.e., distributed transactions) suffers from a variety of problems:

- Performance problems when leveraging Distributed Transaction Coordination technology like XA Transactions or Microsoft DTC (i.e., 2-phase commits).

- Complexity when using patterns like Saga pattern and/or Compensating Transaction pattern.

Designing your Aggregate Roots perfectly doesn’t guarantee you won’t need some of those patterns. However, it will minimise how often you need them.

In summary, if your microservice setup splits an aggregate root, you are doing it wrong; you should “merge” those two services.

Rule 4 – Network latency adds up

Crossing the network is one of the slowest operations. It also introduces massive uncertainty and new failure scenarios compared to running a single process in the same memory space. Jonas Boner has a fantastic talk about the “dangers” of networks’ non-deterministic behaviour compared to the “consistency” one can expect from in-memory communication.

This is true when you call other microservices (e.g., directly via REST or indirectly via asynchronous communication) and when talking to external infrastructure dependencies like databases.

When considering “dividing” your system into multiple microservices, consider the impact on end-to-end latency against any non-functional requirements for latency (e.g., 99th percentile latency).

Rule 5 – No Service to Service calls between services

This rule only applies if you are following a strict “Event Driven Architecture”. Even if that scenario, there will be cases where S2S calls will be “necessary” to avoid unnecessary complexity.

One of the benefits of microservice architecture is the decoupling that we get from services that

depend on each other indirectly. In a monolith, all modules live and fail together, causing a large “blast radius” when something goes wrong (i.e., the whole thing fails).

In traditional microservices (e.g., sync communication based via REST/HTTP or gRPC), there is a decoupling in “space” (i.e., the services don’t share the same hardware). However, they are still coupled “in time” (i.e., to an extent, they all need to be healthy for the system to perform). Some patterns, like circuit breakers, aim to mitigate this risk.

Avoiding S2S calls breaks the couple “in time” by introducing a middleware (e.g., message broker, distributed log) that guarantees producers and consumers don’t need to be online simultaneously, only the middleware. This middleware software tends to be designed to be highly available and resilient to network and software failure. For example, Kafka has some parts verified using TLA+.

To sum up, “forcing” microservices to communicate asynchronously causes teams to consider their architecture in terms of:

- Eventual consistency

- Asynchronous communication

- Commands and events exchanged between them

This leads to more resilient, highly available systems in exchange for (potential) complexity. If you follow the principles of the Reactive Manifesto, you’ll consider this a staple. However, it might feel technically challenging if you are used to n-tier monoliths sitting on an extensive Oracle/SQLServer database.

Conclusions

There are a few hard rules that one must always follow in anything related to building software. It is such a contextual activity that, for every question, there is almost always an “It depends” answer. That said, having a target architecture, a north star that the team collectively agrees to aim for, is good. When it is not followed, some analysis (ideally recorded for the future) should be done about why a decision was made against the “ideal” design.

In this post, I proposed a few rules I tend to follow (and recommend) when building microservices. Sometimes, it will make sense to break them; however, if you find yourself breaking them “all the time”, you might not be doing microservices in anything other than the name (and that, too, could be okay, but just call it what it is :))