When I entered the software industry a long time ago, people who had been part of it warned me that software trends came and went and eventually returned. “This thing that you call ‘new’, I have seen it before”. I refused to believe it. Like a wannabe Barney Stinson, I thought ‘new’ was always the way.

I have been around long enough to see this phenomenon with my own eyes. In this series of posts, I want to call out a few examples of “trends” (i.e., new things) that a) aren’t new anymore and b) people are walking away from. The series starts with one of the most “controversial” trends in the last 10-15 years: microservices!

Microservices are so 2010s

Microservices are dead! I’m joking. They are not dead, but they are not the default option anymore. We are back to… monoliths.

While there have always been people who thought microservices weren’t a good idea, the inflexion point was the (in)famous blog post from Amazon Prime video about replacing their serverless architecture with a good, old monolith (FaaS is just an “extreme” version of microservices).

Why was this more significant than the thousands of posts claiming microservices were unnecessary complexity, talking about distributed monoliths and criticising an architectural approach that came from FAANG and only suited FAANG? Well, because… it came from FAANG. The haters could claim that even a FAANG company had realised microservices weren’t a good idea (“We won!”).

Realistically, this would have been anecdotal if it weren’t for something more important than a bunch of guys finding a way to save money when they serve millions of daily viewers (do YOU have THAT problem?).

It’s the economy, stupid

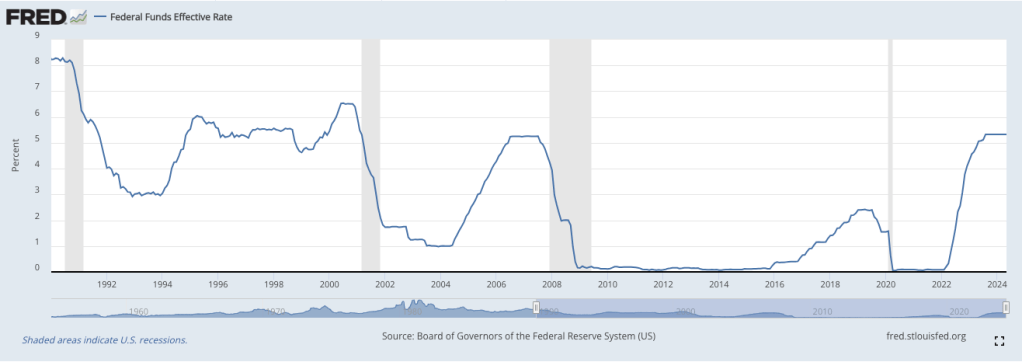

The image above shows the US FED official interest rates. Historically, interest rates have been pretty high (about 5%, according to a recent interview with Nassim Taleb on Bloomberg). From 2008 to post-COVID 2022, we experienced an anomaly: close to 0% rates for almost 15 years. Investors desperate to find good returns for their money poured billions on tech companies, hoping to land the next Google or Facebook/Meta.

Lots of startups with huge rounding funds started to cosplay as future members of the FAANG club: copy their HR policies, copy their lovely offices, and, of course, copy their architectural solutions because, you know, we are going to be so great that we need to be ready, or we might die of success.

We all built Cloud Native systems with Share-Nothing architectures that followed every principle in the Reactive Manifesto and were prepared to scale… to the moon! 🚀 Microservices were the standard choice unless you were more adventurous and wanted to go full AWS Lambda (or a similar FaaS offering) and embrace FinOps to its purest form.

The only drawback is that it was expensive (let’s ignore complexity for now, shall we?). That didn’t matter when the money was flowing, but now the music has stopped, and everybody is intensely staring at their cloud provider bill and wondering what they can do to pay a fraction of it.

What is next?

Downsizing all things.

| Before | After | Comment |

| Microservices/FaaS | Monolith(s) | “Collapse” multiple codebases into one and deploy as a single unit. The hope is that teams have become more disciplined at modularising (unlikely) and “build systems” have become more efficient in managing large codebases (possibly). |

| Messaging (Kafka et al) | Avoid middleware as much as possible | Middleware is expensive technology. With monoliths, there will be fewer network calls that require it. Direct communication (e.g., HTTP, gRPC) will be the standard (again) when necessary. Chuckier monoliths will reduce network traffic compared to microservices |

| NoSQL | Relational | Many NoSQL databases optimise for high throughput / low latency / high durability, which will happily be sacrificed for cost savings. Relational databases are easier to operate and run yourself (i.e., self-host), which is the cheapest option (some NoSQL, like CosmosDB or DynamoDB, can’t be self-hosted). On the complexity side, relational databases are seen as easier for developers to understand (until you see things like this). |

| Stream Processing | Gone except for truly big data | Stream Processing is expensive and complex. Most businesses won’t care enough about latency to pay for it, nor will have volumes that require it. |

| Kubernetes | Cloud-specific container solutions | We should see a transition towards more “Heroklu-like” execution platforms. It will be a tradeoff between flexibility (with K8S offers bucketloads) and cost/simplicity. Sometimes, containers will be ditched too and replaced by language-specific solutions (like Azure Spring Apps) to raise the abstraction bar even higher. |

| Multi-region / Multi-AZ deployments | No multi-region unless compliance requirement. Fewer multi-AZ deployments | Elon has proved that a semi-broken Twitter is still good enough, so why wouldn’t companies building less critical software aim for 3-5 9s? |

| Event-Driven Architecture | Here to stay | This approach isn’t more or less expensive than Batch Processing (if anything, it’s cheaper) and still models business flows more accurately. |

What are we gaining and losing?

Microservices are neither the silver bullet nor the worst idea ever. As with most things, they have PROs and CONs. If we ditch them (or push back harder against their adoption), we will win things and lose things.

What do we win?

- It is easier to develop against a single codebase.

- Local testing is simpler because running a single service in your machine is more straightforward than running ten. Remote testing is also more accessible, as hitting one API is less complicated than hitting many across the network.

- It is also easier to deploy a single service than many.

- Easier maintainability/evolvability. When a business process has been incorrectly modelled, it is easier to fix on a monolith (with, ideally, single data storage) than across many services with public APIs and different data storages.

What do we lose?

- Once a codebase is large enough, it is tough to work against it. Software is fractal, which is also valid for “build systems”: you want to divide and conquer.

- Deploying a single service can be more challenging if multiple people (or, even worse, teams) need to release changes simultaneously. More frequent deployments can alleviate the problem, but most companies don’t go from a

devbranch to PROD in hours but days/weeks. - The blast radius for incorrect changes will be higher. Systems are more resilient when they are appropriately compartmentalized.

- Organisations growing (are there any left?) will struggle to increase their team’s productivity linearly with the headcount when the monolith becomes the bottleneck for all software engineering activities.

- FinOps and general cost observability against business value will massively suffer. A single monolith will lump everything together. With multiple teams involved, it will be harder to understand who is making good implementation decisions and who isn’t, as the cost will be amalgamated into a single data point.

Summary

Microservices are not dead. However, they are suspicious because they are expensive in terms of infrastructure cost and, indirectly, engineering hours due to their increased complexity. However, they are also crucial to unlocking organisational productivity as the engineering team grows beyond a bunch of guys sitting together.

As the industry turns its back to FAANG practices and we sacrifice various “-ilities” on the altar of cost savings, the future of microservices will be decided based on how often we identify when they are the absolute right solution and how well we articulate its case. When in doubt, the answer will be (and perhaps it should have always been) ‘NO’.

As a parting thought, I have been involved in 3 large-scale monolith refactors/rewrites to microservices. All these projects were incredibly complex, significantly delayed and more of a failure than a success (some never entirely completed). Starting with a monolith is, most of the time, the correct answer. However, delaying a transition to smaller, independent services is almost always as bad (if not worse) than starting with microservices would have been in the first place. We are entering a new era where short-time thinking will be even more prevalent than before.